Medical Malpractice Lawyer in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Heather Mitchell

When it comes to seeking justice in the wake of medical negligence, having a compassionate and experienced attorney is essential. Heather Mitchell, a trusted medical malpractice lawyer in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, has built a reputation for delivering exceptional legal representation to those affected by healthcare provider errors. If you or a loved one has been the victim of medical malpractice, Heather Mitchell is the advocate you need to fight for your rights.

When it comes to seeking justice in the wake of medical negligence, having a compassionate and experienced attorney is essential. Heather Mitchell, a trusted medical malpractice lawyer in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, has built a reputation for delivering exceptional legal representation to those affected by healthcare provider errors. If you or a loved one has been the victim of medical malpractice, Heather Mitchell is the advocate you need to fight for your rights.

Why Choose Heather Mitchell for Your Medical Malpractice Case?

Medical malpractice cases are among the most complex areas of law, requiring in-depth knowledge of both legal and medical systems. Heather Mitchell brings years of expertise and a personalized approach to every case. Here are just a few reasons why she stands out as a leading attorney in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma:

1. Extensive Experience

Heather Mitchell has successfully handled numerous medical malpractice cases, ranging from surgical errors and misdiagnoses to medication mistakes and birth injuries. Her in-depth understanding of medical malpractice laws in Oklahoma enables her to build compelling cases on behalf of her clients.

2. Client-Centered Approach

Heather takes the time to listen to her clients’ stories, understand their unique circumstances, and provide tailored legal guidance. Her dedication to her clients’ well-being ensures they feel supported throughout the legal process.

3. Proven Results

With a track record of securing favorable outcomes, including settlements and trial verdicts, Heather Mitchell has helped countless families recover the compensation they deserve. Her ability to navigate complex medical evidence and negotiate with insurance companies is unmatched.

4. Local Expertise

As an Edmond-based attorney, Heather Mitchell is deeply familiar with the Oklahoma legal system and local courts. This familiarity allows her to provide strategic, effective representation for her clients.

Common Types of Medical Malpractice Cases Heather Mitchell Handles

Medical malpractice can occur in various forms, and Heather Mitchell has the expertise to address a wide range of issues, including:

Surgical Errors:

Mistakes during surgery, such as operating on the wrong site or leaving surgical instruments inside the body, can have devastating consequences.

Misdiagnosis or Delayed Diagnosis:

Failing to diagnose a condition promptly can lead to worsening health and even preventable death.

Medication Errors:

Incorrect prescriptions, dosages, or drug interactions can cause severe harm.

Birth Injuries:

Errors during childbirth can lead to long-term disabilities for both mother and child.

Anesthesia Mistakes:

Improper administration of anesthesia can result in life-threatening complications.

What to Expect When Working with Heather Mitchell

When you choose Heather Mitchell as your medical malpractice lawyer, you can expect a seamless and transparent legal process:

1. Initial Consultation: Heather provides a free consultation to review your case and determine if medical negligence occurred.

2. Comprehensive Case Review: She works with medical experts to analyze records and gather evidence.

3. Filing a Claim: Heather will file a legal claim and represent you in negotiations or court proceedings.

4. Fighting for Fair Compensation: She aims to secure compensation for medical expenses, lost wages, pain and suffering, and more.

Contact Heather Mitchell Today

If you’re searching for a skilled medical malpractice lawyer in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Heather Mitchell is the attorney you can trust. She is committed to helping victims of medical negligence receive the justice they deserve. Contact her office today to schedule your free consultation and take the first step toward recovery.

Medical malpractice can have life-altering consequences, but you don’t have to face the aftermath alone. With Heather Mitchell by your side, you’ll have a dedicated advocate who will fight tirelessly for your rights. Reach out to her today and experience the difference a compassionate and skilled attorney can make.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

The health care industry needs to be more honest about medical errors.

Twenty years ago this fall, the Institute of Medicine—an U.S.-based independent, nongovernmental organization widely regarded as an authority at the intersection of medicine and society—released a report titled “To Err Is Human.” It announced that up to 98,000 Americans were dying each year from medical errors.

Official and popular reaction was swift. Congress mandated the monitoring of progress in efforts to prevent patient harm, and the health care industry set grand goals, such as reducing medical errors by 50% within five years. News outlets reported on the proceedings closely. A remedy for a longstanding problem seemed in sight.

Yet, in 2019, medical errors are about as prevalent as in 1999. “To Err Is Human” was an uneasy read; so is a September 2019 report on patient safety from the World Health Organization. Among WHO’s findings: Globally, hospital-acquired infections afflict about 10% of hospitalized patients. Medical errors harm some 40% of patients in primary and outpatient care. Diagnostic and medication errors hurt millions, and cost billions of dollars every year.

So, two decades on, why this chronic state of risk in health care?

The chain reaction to the 1999 report spent its energy quickly. Contrary to the report’s calls for expertise from outside the medical profession, patient safety was taken over by clinician managers and other health care administrators whose interests would hardly have been served by a thorough consideration of the crisis that would have rattled the status quo. These institutional leaders also brushed off experts (psychologists, sociologists, and organizational behaviorists, among others) who have long offered innovative ideas for improving safety and reducing health care mishaps.

The medical managers had ideas, too, but those amounted to localized—and weak—prescriptions like safety checklists, hand-sanitizing stations, posters promoting “a culture of safety,” and programs inviting low-level staff members to speak up and speak their minds to their supervisors. Absent were innovations aimed at bigger classes of hazards beyond the scope of even large, multi-hospital systems such as resolving problems like look-alike, sound-alike drugs, or of confusing and error-inducing interfaces in technology.

Look-alike sound-alike drugs are medications that have spelling similarities or are visually similar in physical appearance or packaging. For example, mixups in the medications “epinephrine” and “ephedrine” have led to much patient harm. The drug names look similar and are sometimes stored close to each other. But each drug has a different purpose and can have serious adverse and even deadly effects if administered incorrectly. Error-inducing technology interfaces occur when simple technology connecting devices fit multiple tubes, outlets, or machines, increasing the possibility of misconnections. For example, when a feeding tube is mistakenly coupled with a tube that enters a vein, or an IV tube is inadvertently connected to the nasal oxygen.

Patient safety can be tricky to define, because it’s essentially a non-event. When things are going well, no one wonders why. When a mistake occurs and threatens the unrealistic “getting-to-zero” goal of many health care managers, then it becomes an event that demands a reaction. And the reaction generally is to assign blame to people further down the organizational ladder.

It’s far easier, after all, for the industry to fault individual workers on the front lines of medical care than to scrutinize inherent organization and system flaws, or to finger highly paid specialist doctors. In the current approach to patient safety, the focus—on who did wrong and how they did wrong—is misplaced. Instead, it should be on what’s going right and what lessons can be learned from those successes.

This is how health care organizations and the industry as a whole avoid dealing with the troubling task of identifying root causes of the patient-safety problem. Meanwhile, the public is assured there is little to fear (and little need for external intervention), because, after all, health care professionals are on the job.

But clinician leaders and hospital administrators in charge of the industry need to realize that health care, including its patient safety component, is too big and too complex to be steered by medical professionals only. We live in an era of multifaceted problems that call for multidisciplinary approaches. Advances in anesthesia safety, for example, would not have come without the input of engineers. Experts with perspectives from outside of medicine should be welcomed to any serious discussion of how to improve patient safety, and their insights heeded.

Let the words of human-factors engineering pioneer John Senders help guide a truly reformed patient safety movement: “Human error in medicine, and the adverse events that may follow, are problems of psychology and engineering, not of medicine.”

An important social movement seemed to emerge in the wake of “To Err Is Human,” but it has lost its way. By being bolder and more comprehensive in its goal setting, and by embracing the acumen of experts from outside the medical profession, the health care industry could make patient safety the great social movement it deserves to be.

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

Retained Surgical Items: Definition and Epidemiology.

View more articles from the same authors.

Background

Prudent medical practice and federal and state laws require that any surgical item not intended to remain inside a patient be removed. When a surgical item is not removed, it is referenced as a retained surgical item (RSI). Surgical items are supplies and devices used in or around a surgical or procedural site, wound, or incision that are used to aid in the performance of an operation or procedure, to provide exposure or coverage, or to absorb blood and other body fluids. These items are NOT “foreign” bodies or objects; they are supplies or devices that the hospital or facility purchased and were intentionally used by the operating room (OR) staff in the delivery of care. By contrast, foreign bodies or objects refer to external items that an individual may ingest, insert, aspirate, or be shot or stabbed with. Examples include ingested batteries, dentures, safety pins, screws and other sharp objects, inserted sex toys, bullets, shrapnel, and polymer projectiles. Surgical intervention may be needed to remove a retained foreign object (RFO) or retained foreign body (RFB) that is found within the body.

Retention of a surgical item refers to possessing, keeping, or holding onto it; this word implies that the surgical item was not intended to remain in the patient. For example, when reducing and repairing a fracture using plates or screws, the final construct is not considered to be “retained hardware”. The term “retained hardware” would only be used if some piece or part of the construct was supposed to be removed but was not. Therefore, the term “RSI” does not require a modifier, such as inadvertent, unintended, or accidental. If an item such as wound packing or a wound vacuum system or a vascular clamp is intentionally placed for treatment or therapy and intended to temporarily remain in a patient after the procedure, the preferred terminology is “therapeutic packing” or placement. If that therapeutic pack is not removed as intended, then it should be described as a “retained surgical pack” rather than as “unintentional retention of an intentionally retained pack.”

With the above considerations in mind, the term “retained surgical item (RSI)” is clearly preferred over older terms such as RFO, RFB, inadvertent RFO or RFB, or unintentional RFO or RFB. Although RSI is also an abbreviation for the anesthesia procedure, “rapid sequence induction,” confusion is unlikely given the context for using these terms. Clarity of usage will improve reporting, optimize coding, and enhance search engine functionality to provide better information. An RFO or RFB is not the result of medical error, whereas an RSI is a multi-stakeholder patient safety problem and possibly an act of medical negligence. Proper application of the terms RSI and RFO/RFB will identify different elements of causation and different preventive strategies in examining cases.

Taxonomy

RSIs are classified into two groups. Group I includes four (4) classes of surgical items that comprise a traditional “surgical count” performed by operating room (OR) staff: surgical sponges and surgical towels, sharps, small miscellaneous items (SMI), and instruments. Group II includes dressings and drape towels, devices used during operations and procedures, and device fragments that result from breakage or separation of a device. This group also includes multi-component implant systems. These group II items are not usually managed with a “surgical count”. The table below provides detailed examples from each group.

| Group I | |

| Surgical sponges | Soft items made of white (bleached) cotton, woven fabric or gauze that contain x-ray detectable markers and are used within surgical wounds. Surgical sponges include but are not limited to laparotomy pads (18”x18”), mini laps (12”x12”), baby laps (4”x18”), radiopaque 4”x4” or 4”x8” sponges, tonsil or round sponges, peanut or “cigarette” sponges, and neurosurgical patties. |

| Surgical towels | Large (16”x26”) woven cotton towels used in the OR and procedure areas. Surgical towels ALWAYS have X-ray detectable (radiopaque) markers. Only white (bleached) surgical towels are used intra-corporally (i.e., inside a patient), and must be counted. |

| Sharps | Metallic, pointed or cutting objects of various sizes that include but are not limited to suture needles, scalpel blades, hypodermic needles, and hooked knife blades. |

| Small miscellaneous items (SMI) | Other objects used during surgical procedures that are often single use, often not radiopaque, may be composed of multiple parts, and may include but are not limited to electrosurgical scratch pads, electrocautery tips, vessel loops, rubber shods, suture booties, umbilical tapes, laparoscopic or thoracoscopic ports, disposable instrument inserts, cotton-tip applicators, marking pens, suture reels, screws, nails, safety pins, endoscopic clip appliers, bulldog clamps, vascular inserts, hemostatic materials, nasal suction bulbs, bulb syringes, and visceral ”fish” retainers. |

| Instruments | Surgical tools designed to perform specific functions such as cutting, dissecting, grasping, holding, suturing or retracting. These items are usually stored and sterilized in surgical trays and individually may have multiple parts. They are usually metallic and radiopaque. Examples include, but are not limited to clamps, needle holders, multi-component retractors, malleable/ribbon retractors, screwdrivers, knife handles, and scissors. |

| Group II | |

| Dressings | Soft items such as gauze sponges or rolls, ribbon packing, nasal packs and other packing material, prep swabs, iodoform gauze, nonadherent pads, and polyurethane foam sponges for vacuum-assisted wound care. These soft goods are usually applied at the end of a procedure to cover or provide hemostasis in a wound. They are intended to be changed or removed at another site by personnel other than an OR nurse or surgical technologist. They are not considered part of a surgical count because they are managed outside the domain of OR staff. |

| Drape Towels | Drape towels are usually blue, green or an unbleached natural color, are made of coarser grade cotton, and are multi-functional. They are primarily used as drapes, wipes or covers. They do not contain radiopaque markers, are not to be placed inside patients, and are not counted. |

| Devices | Devices are any type of equipment or tools that have designated functions used during a procedure that may have electronic or mechanical component parts. Devices include items such as staplers, drains, catheter insertion sets, needle localization sets, vessel sealing apparatus, and stone retrieval kits. |

| Device fragments | Device fragments are broken parts or pieces of tools or devices. Examples include a piece of a drill bit, a broken tip or part of an instrument, a broken part of a catheter or drain, a fragment of a stent, or the tip of a guidewire. |

| Implant Systems | Instrumentation and individual components arranged on multiple preset trays that are required for reconstructive bone and joint surgery, and certain audiologic and cardiovascular device implantations. These implant systems are frequently loaned from a vendor for a specific case or procedure and are referred to as “loaner trays or instrumentation.” A single system may be composed of multiple trays, each holding parts such as instruments, sizers, trials, inserts and liners used to measure and prepare the implantation site. The specific non-biological implantable devices, which are also part of the systems, are then opened and inserted to create the final surgical construct. |

| Trial devices, inserts, or sizer component parts | Surgical tools used to measure and prepare a site for the insertion of a compatible, non-biological, implantable device. These surgical tools are often multiple, arranged on pre-designed trays, made of plastic or dense polymer, and may not be radiopaque. |

A patient with a retained device, needle, sponge, instrument, dressing or SMI is generally considered to have experienced a “never event”, a safety event that is never supposed to happen. All RSI cases are usually required to be reported to internal hospital risk management and patient safety incident reporting systems. Some RSI cases qualify as reportable adverse events [called serious reportable events (SRE) by the National Quality Forum (NQF) or sentinel events by The Joint Commission (TJC)], triggering notification to external entities. There are three general entities for external reporting:1 (1) mandatory reporting to state licensing or public health authorities; (2) voluntary reporting to Patient Safety Organizations (PSOs), collaborations authorized under the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005; and (3) voluntary reporting to regulatory, accreditation, or certification agencies, such as The Joint Commission. All entities agree that an item is retained if found in a patient “after surgery”. However, the precise definitions of “after surgery” or “after surgery ends” differ somewhat.

Most states that require mandatory event reporting, the American Hospital Association Coding Clinic, and thus the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) follow the NQF SRE 2011 guidelines, which state that surgery ends: “(1) after all incisions or procedural access routes have been closed in their entirety, (2) devices have been removed, (3) final surgical counts have concluded and any discrepancies resolved, and (4) the patient has been taken from the operating room.” A vaginal birth ends when the mother is in the immediate recovery period (1-2 hours post birth). These conditions are closely analogous to traditional OR record designations for: procedure start time (incision/cut time), procedure finish time (closed time), and “out of OR” time. In other words, “after surgery ends” corresponds to the period after “out of OR,” NOT the period after incisional closure, because the operation isn’t over until the patient leaves the OR.

Part 3 of the above definition is particularly important because of how surgical counts are performed and any discrepancies are resolved. In some cases, the surgical team is still looking for an item that they know is missing, but they have exhausted the ability to find it in the OR. For example, if plain radiographs have not been helpful, the team may decide to get computed tomography (CT) images, or they may transfer the patient to the intensive care unit (ICU), where additional assistance for patient safety and monitoring is available. In these cases, any items discovered through subsequent imaging would not be considered retained or reportable because known discrepancies had not yet been resolved, and in fact, the team was using best practices to solve the problem.

In contrast to NQF, TJC opines that “after surgery” includes any time after completion of the wound skin closure, even if the patient is still in the OR under anesthesia. This definition is not accepted by the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) or the American College of Surgeons (ACS). Indeed, many healthcare facilities use the NQF definition while others use the TJC definition for reporting, but all follow the NQF definition for ICD-10-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification) coding and reimbursement for care. Clearly, using one definition vs the other will yield a difference in the number of RSI events.

Epidemiology

Not all RSIs are required to be externally reported, which influences the reported incidence of RSI cases. Specifically, “unretrieved device fragments (UDF)” are not usually considered SREs or sentinel events, so they are rarely reported to external systems. These items are unretrieved because a clinical determination has been made by the provider that the risk of removing the object exceeds the risk of leaving it where it is. In these cases, there is still internal organizational reporting where the organization (1) discloses to the patient the presence of the unretrieved device or device fragment and (2) keeps a record of cases to identify trends and patterns (for example, by type of procedure, by type of retained item, by manufacturer, by practitioner) that may highlight opportunities for improvement. In addition, surgical drains and guidewires (most commonly in central veins) are devices that are not counted but may be retained during insertion or may break upon removal. These occurrences are considered device retention events (i.e., retained device fragments) and may require an operation or procedure for removal, if the risk of removal is less than the risk of retention. Incorrect counts of surgical needles are common and frequently remain unresolved, with little available information about the frequency of actual retention of suture needles. Therefore, careful examination of what RSI are being discussed in RSI estimates is warranted.

With the above caveats in mind, the incidence of RSIs has been estimated as 1.3 per 10,000 surgical procedures, according to a systematic review of 21 incidence studies. These rates vary somewhat based on whether the data originate from external reporting systems or from internal (facility reporting) sources and what the system reporting rules are with specificity to what types of surgical items are required to be reported.

For example, data from one of the best state reporting systems provides information about the relative distribution of RSI cases. California started public reporting of all RSI events in 2007 with possible administrative penalties assessed after investigation of confirmed events. In an evaluation conducted by Verna Gibbs, MD (email communication, December 2023), the 79 cases that received administrative penalties from 2007-2011 were distributed as follows:

- 46 cases (58%) involved surgical sponges or towels.

- 30 lap pads, 13 radiopaque textile (4×4) sponges, and 3 towels

- 13/46 (28%) of these cases came from obstetric or gynecology areas.

- 0 cases involved sharps (indicating that needles/sharps either are not retained or were not reported, because they were not retrieved and were not considered to cause harm).

- 24 cases (30%) involved SMI and device fragments.

- 9 cases (11%) involved instruments.

- 7/9 cases involved one type of instrument – a malleable/ribbon retractor.

Retained sponges are the most frequently reported surgical item to cause patient harm because these cases require a second operation for sponge removal, which is considered harm. Increased appreciation of the problem of retained vaginal sponges and other items (e.g., vaginal packing) left behind after spontaneous vaginal births, as well as the frequent retention of lap pads after cesarean births, has brought increased recognition to these areas as opportunities for improvement. UDFs are often the most frequently reported to internal facility reporting systems (with drill bits lodged in bone as the most common type of UDF), but these events are rarely reported to external systems. Instruments are very rarely retained even though hundreds of instruments are opened and used during some operations. Needles are the most frequently miscounted surgical item, but their relative contribution to the problem of RSIs is unclear. Individual facilities and healthcare entities have reported improvement in the incidence of specific types of RSI cases, such as retained surgical sponges, but it is unclear whether this incidence has decreased over time nationally and whether the finding is generalizable to all types of RSI.

Known risk factors for RSIs, according to a 2014 meta-analysis of three studies, include intraoperative blood loss greater than 500 mL; duration of operation; more than one sub-procedure; failure to perform surgical counts; involvement of more than one surgical team; and unexpected intraoperative factors or events. The occurrence of any safety variance, and specifically an incorrect count at any time during the procedure, has been repeatedly associated with elevated RSI risk. Obesity may be a risk factor specifically among patients who have an abdominopelvic operation. These observations suggest that there are opportunities for practice improvements in the environments where procedural and surgical care is provided.

Verna Gibbs, MD

NoThing Left Behind ®

drgibbs@nothingleftbehind.org

Patrick Romano, MD, MPH

Co-Editor-in-Chief, AHRQ’s Patient Safety Network (PSNet)

Professor

Department of Internal Medicine, Division of General Medicine

UC Davis Health

psromano@ucdavis.edu

References

- West N, Eng T. Monitoring and reporting hospital-acquired conditions: a federalist approach. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2015;4(4):mmrr2014-004-04-a04. Published 2015 Jan 6. [Free full text]

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

The Different Types of Medication Errors

Source: National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519065/

Source: National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519065/

Rayhan A. Tariq; Rishik Vashisht; Ankur Sinha; Yevgeniya Scherbak.

Author Information and Affiliations

July 3, 2022.

Types of Medication Errors

-

Prescribing

-

Omission

-

Wrong time

-

Unauthorized drug

-

Improper dose

-

Wrong dose prescription/wrong dose preparation

-

Administration errors include the incorrect route of administration, giving the drug to the wrong patient, extra dose, or wrong rate

-

Monitoring errors such as failing to take into account patient liver and renal function, failing to document allergy or potential for drug interaction

-

Compliance errors such as not following protocol or rules established for dispensing and prescribing medications

Clinical Significance

Medication errors are a common issue in healthcare and cost billions of dollars nationwide while inflicting significant morbidity and mortality. While national attention has been paid to errors in medication dispensing issues, it remains a widespread problem. The best method to enhance patient safety is to develop a multi-faceted strategy for education and prevention. Emphasis should be put on healthcare providers working as a team and communicating as well as encouraging patients to be more informed about their medications. With a culture of safety, dispensing medication errors can be reduced.

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

Factors affecting the recurrence of medical errors in hospitals and the preventive strategies: a scoping review

Medical errors are unavoidable occurrences in health systems that can adversely affect patient safety (1) . Years after the American Institute of Medicine’s prominent report, “To Err Is Human” (2) , which addressed the importance of medical errors for the first time, there are still serious concerns about patient safety (3) .

Medical errors are unavoidable occurrences in health systems that can adversely affect patient safety (1) . Years after the American Institute of Medicine’s prominent report, “To Err Is Human” (2) , which addressed the importance of medical errors for the first time, there are still serious concerns about patient safety (3) .

Patient safety is a fundamental right that must be guaranteed when visiting or hospitalizing patients. It is rather significant to investigate the possible causes and preventive measures for medical errors. In addition, medical error prevention can help to reduce adverse after-effects such as permanent disability, complications and death (4) . Clinicians have the moral obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harm while providing treatments or services to patients. Clinicians also have an ethical responsibility not to inflict harm on patients intentionally or through carelessness (5) . Preventing medical errors requires the establishment and management of value-based ethical environments. Such environments describe ethical policies that focus on employee’s commitment to values and norms related to practices (6) .

As reported by the Institute of Medicine, an estimated 44000 – 98000 deaths in the USA every year are attributed to medical errors (2) . Patient safety and quality of care are seriously affected by medical errors in hospitals. The epidemiology of medical error injuries remains a pressing global issue. In the United States, a recent report reviewing previous studies ranked unpleasant occurrences, especially medical errors, as the third leading cause of death (7) . In particular, up to 1.1% of hospital admissions have resulted in deaths due to medical errors. In 2013, more than 400,000 deaths were caused by medical errors (8) . In the UK, 101 medication errors occur per 1,000 drug prescription cases (9) , and it is also estimated that drug errors cause 12,000 deaths per year according to the National Health Service (NHS) (10) . The number of reported events increased from 135,356 between October and December 2005 to 508,409 during the same period in 2017 (11) .

Over the years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed patient safety guidelines to prevent medical malpractice, including Preventing Patient Fall , patient identification, hand hygiene, and safe surgery (12) . The Joint Patient Safety Group has introduced several patient safety goals to help healthcare providers create a safer environment for patients as well as themselves (13) . However, despite these efforts, the rate of medical errors leading to disability and significant mortality is high (14) . Moreover, we still encounter errors that have detailed guidelines dedicated to them and should not keep recurring. While emphasizing the enormous burden of harm to patients seeking treatment, the World Health Organization has stated that over the past 15 years, global efforts to reduce harm to patients have not been effective despite pioneering work in some healthcare centers (15, 12) .

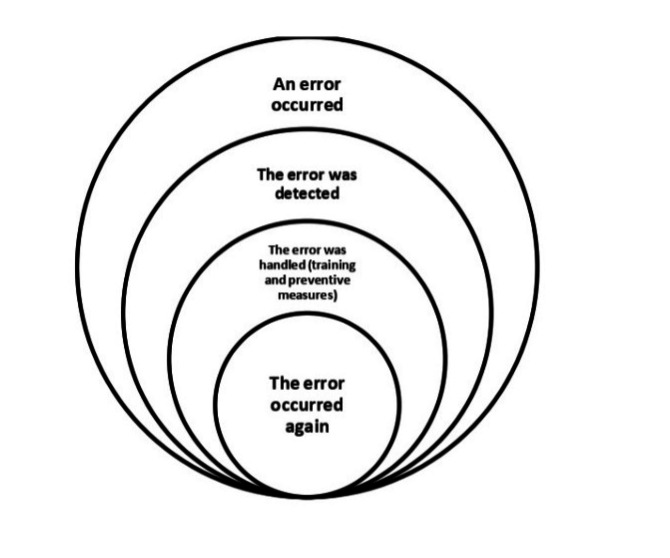

Recurrence of errors in this study refers to errors that 1) have been discovered once in the study environment, 2) are caused by factors that have been analyzed and for which specific preventive guidelines exist, and 3) continue to occur in spite of training and sensitization (Figure 1).

It appears that the measures currently being taken to reduce medical errors are not sufficiently coherent and need to be reviewed to prevent the recurrence of errors that occur frequently. Given the widespread efforts that have been made to prevent medical errors worldwide, the high frequency of errors has led to the hypothesis that there may be factors other than those currently known. Therefore, a scoping review was needed to identify the factors that have been considered at the international level in the field of error recurrence. This study aimed to identify international actions regarding factors related to the recurrence and prevention of medical errors in hospitals and to identify any existing knowledge gaps.

Two groups of results were found in the present study: A) Factors related to the recurrence of medical errors, and B) Strategies to prevent the recurrence of medical errors.

A) Factors related to the recurrence of medical errors

Two categories of human, and environmental and organizational factors were identified, along with six items, explained below.

Human factors

Fatigue: In some studies, fatigue has been identified as the most important cause of error and its recurrence (19, 23, 31). In one study, fatigue was reported as a contributing factor to anesthesia errors (28). Also, high workload and insufficient sleep lead to fatigue, which increases the frequency of mistakes (19,27, 30).

Stress: According to studies, stress is one of the most important factors in the occurrence and recurrence of medical errors (19, 23, 27, 42). We also found that people with neuroticism (including anxiety, anger, irritability, vulnerability and depression) were more likely to make medical errors (37).

Inadequate knowledge: Insufficient knowledge and skills are the most common cause of medication errors (21). In addition, inadequate knowledge can lead to stress and fatigue and increase medical errors (23). Studies conducted in the neonatal ward and operating room have shown that lack of sufficient knowledge and skills leads to the recurrence of medical errors (25, 43).

Environmental and organizational factors

Ineffective management: In this category, the following factors were found to lead to medical error recurrence: existence of strong authority in the organization that suppresses the possibility of identifying and learning from errors (43); expansion of hierarchical boundaries in an organization (such as a hospital) that requires a team structure (28); failure to provide timely and correct patient safety instructions and the results of Root Cause Analysis (RCA) to stakeholders (28, 38); lack of formal oversight of the implementation of safety protocols, and their failure to become an automatic part of the workflow of employees (28); not considering reminders (such as system alarms) and dependence on incomplete human memory, (28).

Various distractions: According to the studies, distraction of the medical staff caused by unnecessary visits to hospital wards, unnecessary telephone calls, staff irregularities, and irregular placement of equipment and medications, leads to surgical, anesthesia and medication errors (18, 23, 31).

Poor teamwork: Poor team communication is one of the most important factors in error recurrence and may cause harm to patients (25, 31, 43). Such weak connections are usually due to poor teamwork between physicians and nurses, which endangers patient safety (25, 43).

B) Strategies to prevent the recurrence of medical errors

According to the studies, six factors were identified as effective in preventing the recurrence of errors, including: 1) use of electronic systems, 2) attention to human behaviors, 3) workplace culture, 4) proper workplace management, 5) training, and 6) paying attention to teamwork.

Use of electronic systems: The findings of several studies have emphasized the importance of using electronic systems such as CPOE (Computerized Provider Order Entry) and barcode systems to prevent the recurrence of errors (14, 19, 21, 23, 28, 32, 46). The barcode system can reduce misdiagnosed drugs, prevent misidentification of the patient and misuse of time, and reduce missed and wrong dose errors (46). Therefore, the installation of barcoded wristbands for all patients should be considered at the time of admission (21). Also, e-prescriptions significantly reduce medication errors and do not put patients at risk for illegible handwriting and related causes (23). Such technologies do not replace specialists involved in patient care, but rather organize information and allow specialists to perform valuable tasks such as complex decision-making and communication while the system performs repetitive and tedious tasks (26).

Attention to human behaviors: Numerous studies have addressed human factors and behavioral issues as a strategy to prevent the recurrence of errors (19, 24, 31, 33, 36, 37, 40, 43). Based on one study, extrovert, conscientious people with strict work ethics committed fewer errors, and those with problem-solving skills did not commit medical errors (37). In addition, the ability to think systematically plays a role in reducing the incidence of medical errors (36). Several studies have found a significant relationship between having a deep understanding of anthropological factors and a reduced amount of incurring “never events” (33, 43). Moreover, in order to eliminate human errors, we should have knowledge of human behaviors and consider the two categories of schematic behaviors and attention-related behaviors. Schematic behaviors are reflective and can be considered in error reduction by using checklists and attracting public attention. Attention-related behaviors, on the other hand, are related to problem-solving skills, and are therefore more difficult to control and require professional supervision and training to reduce errors (34). In some studies, individual and organizational responsibility and accountability have been found to be effective in reducing errors (24, 31, 40).

Proper workplace management: One of the main components of management is supervision. Some procedures that have prevented the recurrence of errors include continuous audits, implementation of powerful documentation such as valid checklists for safe surgery and anesthesia (31, 32, 39), and strict supervision of compliance and corrective measures (28). Proper alignment of forces and increased use of experienced and more educated staff have also been effective in preventing errors. Examples of such measures include increasing the working hours of RN nurses and reducing the working hours of LPN nurses. Also, increasing the number of nurses has reduced the rate of patient fall (13). Hospitals can also help reduce medical errors through stronger and more reliable safety management, including error reporting, learning from errors, information transparency, and providing timely error feedback (23, 43).

Workplace culture: According to studies, medical errors will be reduced in the presence of proper workplace culture (22, 28, 30, 34, 39, 44). In one study, a positive relationship was found between workplace culture and learning from errors (39), and other studies have identified a positive relationship between culture and teamwork (22, 44).

Training: Numerous studies have shown that training in different areas is effective in preventing errors (20, 32, 34, 35, 39, 46). Studies have emphasized the importance of including error training in the university curriculum as part of the education of medical staff to fully acquaint them with the issue before starting work, stating that this will ultimately help reduce medical errors (34, 46). Training campaigns with varied and specific topics in the field of patient safety have been very useful in reducing errors (for instance the campaign of “sign your site”) due to the extent of these campaigns (20, 32, 35). In addition, using educational models such as the Potential Risk Assessment Model (26) and the Eidenhaven Classification Model (14) will improve learning from errors and reduce medical errors. Although RCA is used to provide solutions to prevent the recurrence of errors, it appears that this method cannot prevent errors from recurring (38, 45). One study found that physicians’ participation in RCA recommendations was low (38) and that the RCA often provided recommendations that replicated existing policies or previous recommendations (38, 45).

Paying attention to teamwork: Doing the right thing as a team is effective in preventing mistakes (28, 31, 32, 41, 44). Teamwork is especially significant between physicians and nurses, and in areas such as the operating room and among the surgical team members (28, 31, 37, 41). Therefore, various team-building programs can be used to increase teamwork skills among staff (28).

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

Medication errors in anesthesia: unacceptable or unavoidable?

- PMID: 28236867

- DOI: 10.1016/j.bjane.2015.09.006

Medication Errors

Medication errors are the common causes of patient morbidity and mortality. It adds financial burden to the institution as well. Though the impact varies from no harm to serious adverse effects including death, it needs attention on priority basis since medication errors’ are preventable.

Medication errors are the common causes of patient morbidity and mortality. It adds financial burden to the institution as well. Though the impact varies from no harm to serious adverse effects including death, it needs attention on priority basis since medication errors’ are preventable.

In today’s world where people are aware and medical claims are on the hike, it is of utmost priority that we curb this issue. Individual effort to decrease medication error alone might not be successful until a change in the existing protocols and system is incorporated. Often drug errors that occur cannot be reversed. The best way to ‘treat’ drug errors is to prevent them.

Wrong medication (due to syringe swap), overdose (due to misunderstanding or preconception of the dose, pump misuse and dilution error), incorrect administration route, under dosing and omission are common causes of medication error that occur perioperatively.

Drug omission and calculation mistakes occur commonly in ICU. Medication errors can occur perioperatively either during preparation, administration or record keeping. Numerous human and system errors can be blamed for occurrence of medication errors.

The need of the hour is to stop the blame – game, accept mistakes and develop a safe and ‘just’ culture in order to prevent medication errors. The newly devised systems like VEINROM, a fluid delivery system is a novel approach in preventing drug errors due to most commonly used medications in anesthesia. Similar developments along with vigilant doctors, safe workplace culture and organizational support all together can help prevent these errors.

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

Medical errors: the importance of the bullet’s blunt end

Medical errors are substantial causes of hospital-related morbidity and mortality. It is estimated that preventable medical errors alone cause up to 98,000 annual deaths in the United States—the daily equivalent of one fatal jumbo jet crash [8]. Preventable adverse events and accidents impose a great burden on patients and on the health care system [5]. The finding that medical care in itself may generate harm—sometimes fatal and sometimes persistent—has caused real shockwaves of worrying. The society is not likely to tolerate major accidents in a technologically high standing and expensive activity that is mastered by highly trained professionals and that is intended to heal and not to harm [1]. The adagium primum non nocere (first, do not harm) is one of the principal ethical precepts taught in medical school. However, both unpretentiousness as well as righteous realism point out that in medicine, like in any professional activity, adverse events and accidents may be part of daily practice. Ignoring the fact that also in medicine, Errare humanum est (to err is human) or remaining indifferent to its relevance is nothing less than a sign of dramatic irresponsibility.

Children may be particularly at risk for medical harm. Dependency, limited communication skills, immature anatomy and physiology, the need for age- or weight-adapted equipment, and the need for dosing calculations have all been suggested as potential risk factors [7]. In technically complex health care systems, children’s vulnerability may still be more pronounced. In this issue, Niesse et al. report their analysis of critical incidents (CI) in severely ill children admitted to a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) [6]. Prospectively collected (near) incidents were compared to retrospectively assessed patient data. By use of logistic regression analysis, mechanical ventilation, male gender, and length of stay were identified as significant predictors for the occurrence of (near) incidents. In theory, these finding are interesting, but their practical value remains limited. At first, the three independent predictors that were characterized can hardly be regarded as potential targets for improvement strategies. None of them can effectively be changed or avoided, except by a policy that prevents PICU admissions in general or intubations and invasive ventilation in particular. Recent advances in high-flow oxygen therapy and non-invasive ventilation may partially help to prevent the latter, although these techniques will certainly be associated with their own risk profile. Second, there is no doubt that within a population of sick children, some will be more prone to CIs than others. Recognizing this difference may help in the triage of pediatric patients to the safest possible care. However, since any PICU patient is subject to complex medical care involving many professionals and technical interventions, they all must be considered as being de facto at risk for CIs. This makes it less interesting to identify more precisely those patients who have higher risks, unless one was able to divide the PICU population in, respectively, “no risk at all” and “at risk” subgroups. Since all PICU patients are at risk and individual risk profile may change over time, a CI preventive strategy should be applied to the total population and at all times.

Niesse et al. nicely illustrate the traditional “sharp-end” approach to medical errors by attributing them to directly observable factors on the spot of the actual accident. Although this may work for simple, straightforward systems, it will be insufficient to deal with errors occurring in highly complex systems like medicine. Causes of errors can be situated in individual patients and individual professionals but just as much in factors that are more distant or even unobservably far from the actual working context. Examples of these “blunt end”-situated factors are working conditions (e.g., availability and content of protocols, workload, fatigue due to excessive working hours, professional relations, communication, work atmosphere, importance of hierarchy, reluctance or resistance to report malpractice, etc.), the local policy (e.g., choices of material, lack of appropriate tools, and retrenchments in expenditure), and even legislation. In complex systems, also a “blunt-end” approach is needed in order to reveal the underlying system defect that allowed the opportunity for the error to occur.

A corner stone of quality improvement and error reduction in a “blunt-end” approach is the availability of a continuous and easily accessible tool for error reporting. Niesse et al. nicely illustrate the usefulness of a blame-free CI-reporting system in identifying incidence and characteristics of common CIs. Provider-reported data may have important eye-opening and problem-elucidating effects by offering the opportunities to understand factors that contribute to or prevent harm to patients. Error reporting may lead to the creation of customized interventions that effectively reduce the incidence of errors [2]. In order to make error reporting profitable, some essential preconditions should be fulfilled.

First, the reporting system should apply a low threshold. This means that also near incidents and minor incidents must be reported. Based on experience in high technological industries (e.g., oil industry and civil aviation), it is now widely accepted that it makes more sense to screen systematically for (the much more common) near incidents than to focus only on the analysis of obvious severe accidents. It has been shown that most preventive system changes come from minor incidents that occurred repeatedly over long periods [4]. In my own experience, handling a low threshold also helps professionals to gain experience in dealing with adverse events. This may create an open-debate culture in which reporting (near) incidents becomes an evident part of daily practice.

Second, error reporting should be blame-free. Traditionally, errors are “sharp-end-wise” attributed to individual mistakes, and blamed professionals may be subject to penalization. However, true negligence or guilty neglect is only rarely the major cause of a medical error. Errors need to be considered as system-based phenomena, which are—de facto—impossible to eradicate completely. In order to make the complex medical system safer, it is therefore essential to uncover in time any defects that may lead to major accidents within the foreseeable future. A system that permits admitting errors honestly is more likely to achieve this goal, compared to a punitive approach [3]. Reporting errors should be encouraged as a sign of professionalism and responsibility. Blame-free reporting does not mean that professionals are released from the duty to deliver excellent medical care at all times. Neither should it be considered as an excuse for neglect or negligence.

Third, error reporting should be applied to all levels and professions involved in the patient care and in all possible directions. The most junior team member must be able to correct a senior consultant or to report errors that have been made by superiors, without running the risk of retaliation. This will often require proper teamwork and flattening of existing hierarchies.

Finally, error reporting cannot be an isolated activity. Reported errors must be discussed within a multidisciplinary surveillance group that analyzes the reported (near) incidents, identifies critical situations or processes, implements initiatives for improvement, gives systematic feedback to the front-line professional, and continuously generates incentives for effective reporting by professionals. In addition, health care authorities, both institutional as well as political, must be prepared to accept the consequences of a system-based approach of dealing with medical errors. The failure to improve blunt end-situated causes of medical errors will cause frustration amongst health care workers in the short term and certainly to patient harm in the long term.

References:

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

The High Costs of Misdiagnosis: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions

Have you ever been to a doctor with a health problem, only to find out later that the diagnosis was wrong or delayed? If so, you are not alone. Misdiagnosis is a common and serious problem in medicine that affects millions of patients every year. According to some estimates, up to 20% of medical cases are misdiagnosed, leading to unnecessary suffering, disability, and even death. In this article, we will explore the causes, consequences, and solutions.

Have you ever been to a doctor with a health problem, only to find out later that the diagnosis was wrong or delayed? If so, you are not alone. Misdiagnosis is a common and serious problem in medicine that affects millions of patients every year. According to some estimates, up to 20% of medical cases are misdiagnosed, leading to unnecessary suffering, disability, and even death. In this article, we will explore the causes, consequences, and solutions.Causes of Misdiagnosis

Misdiagnosis can arise from many factors, including:

- Lack of time: Doctors are often under pressure to see more patients in less time, which can lead to rushed or incomplete assessments, missed symptoms, or incorrect interpretations of test results.

- Bias: Doctors may have unconscious biases based on the patient’s age, gender, race, or other factors that can influence their diagnosis and treatment decisions.

- Inadequate training or knowledge: Doctors may not be aware of the latest research, guidelines, or best practices for certain conditions or may lack experience in dealing with rare or complex cases.

- Systemic errors: The healthcare system itself can contribute to misdiagnosis by creating barriers to communication, coordination, or access to information, such as electronic health records that are not user-friendly or not interoperable between providers.

Consequences of Misdiagnosis

- Delayed or wrong treatment: Patients may receive treatments that are ineffective, harmful, or delayed, which can worsen their condition or lead to new complications.

- Emotional distress: Patients may experience anxiety, depression, or other mental health problems as a result of uncertainty, mistrust, or stigma associated with their condition.

- Financial burden: Patients may incur significant costs for unnecessary tests, procedures, or hospitalizations, or lose income due to missed work or disability.

- Legal disputes: Patients may sue doctors or hospitals for malpractice, which can result in costly settlements or damage to reputation.

Solutions to Misdiagnosis

- Improving communication: Doctors should listen carefully to patients’ concerns, ask open-ended questions, and explain the rationale behind their diagnosis and treatment options. Patients should also be encouraged to ask questions, provide accurate and complete information about their symptoms and medical history, and seek second opinions if necessary.

- Using technology: Electronic health records, decision support systems, and telemedicine can enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and accessibility of healthcare delivery, especially in rural or underserved areas.

- Enhancing education and training: Medical schools, residency programs, and continuing education courses should emphasize the importance of diagnostic reasoning, clinical judgement, and teamwork skills, and provide opportunities for feedback, reflection, and improvement.

- Advancing research and innovation: Medical research can generate new knowledge, tools, and therapies that can improve the accuracy and timeliness of diagnosis, such as genomic testing, artificial intelligence, and precision medicine.

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

Adverse Drug Reaction

Source: National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519065/

Source: National Library of Medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519065/

Rayhan A. Tariq; Rishik Vashisht; Ankur Sinha; Yevgeniya Scherbak.

Author Information and Affiliations

July 3, 2022.

The World Health Organization defines an adverse drug reaction as “any response that is noxious, unintended, or undesired, which occurs at doses normally used in humans for prophylaxis, diagnosis, therapy of disease, or modification of physiological function.” Adverse drug reactions are expected negative outcomes that are inherent to the pharmacologic action of the drug and not always preventable, while medication errors are preventable.[7][8][9]

To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System

- PMID: 25077248

- Bookshelf ID: NBK225182

- DOI: 10.17226/9728

Free Books & Documents

Excerpt

Experts estimate that as many as 98,000 people die in any given year from medical errors that occur in hospitals. That’s more than die from motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, or AIDS–three causes that receive far more public attention. Indeed, more people die annually from medication errors than from workplace injuries. Add the financial cost to the human tragedy, and medical error easily rises to the top ranks of urgent, widespread public problems.

To Err Is Human breaks the silence that has surrounded medical errors and their consequence–but not by pointing fingers at caring health care professionals who make honest mistakes. After all, to err is human. Instead, this book sets forth a national agenda–with state and local implications–for reducing medical errors and improving patient safety through the design of a safer health system.

This volume reveals the often startling statistics of medical error and the disparity between the incidence of error and public perception of it, given many patients’ expectations that the medical profession always performs perfectly. A careful examination is made of how the surrounding forces of legislation, regulation, and market activity influence the quality of care provided by health care organizations and then looks at their handling of medical mistakes.

Using a detailed case study, the book reviews the current understanding of why these mistakes happen. A key theme is that legitimate liability concerns discourage reporting of errors–which begs the question, “How can we learn from our mistakes?”

Balancing regulatory versus market-based initiatives and public versus private efforts, the Institute of Medicine presents wide-ranging recommendations for improving patient safety, in the areas of leadership, improved data collection and analysis, and development of effective systems at the level of direct patient care.

To Err Is Human asserts that the problem is not bad people in health care–it is that good people are working in bad systems that need to be made safer. Comprehensive and straightforward, this book offers a clear prescription for raising the level of patient safety in American health care. It also explains how patients themselves can influence the quality of care that they receive once they check into the hospital. This book will be vitally important to federal, state, and local health policy makers and regulators, health professional licensing officials, hospital administrators, medical educators and students, health caregivers, health journalists, patient advocates–as well as patients themselves.

First in a series of publications from the Quality of Health Care in America, a project initiated by the Institute of Medicine

Copyright 2000 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

If you are looking for a Medical Malpractice Attorney in Oklahoma to assist with your case, CONTACT US for a FREE CONSULTATION.

There is NO FEE UNTIL RECOVERY.

1,2

1,2