Medical errors are unavoidable occurrences in health systems that can adversely affect patient safety (1) . Years after the American Institute of Medicine’s prominent report, “To Err Is Human” (2) , which addressed the importance of medical errors for the first time, there are still serious concerns about patient safety (3) .

Medical errors are unavoidable occurrences in health systems that can adversely affect patient safety (1) . Years after the American Institute of Medicine’s prominent report, “To Err Is Human” (2) , which addressed the importance of medical errors for the first time, there are still serious concerns about patient safety (3) .

Patient safety is a fundamental right that must be guaranteed when visiting or hospitalizing patients. It is rather significant to investigate the possible causes and preventive measures for medical errors. In addition, medical error prevention can help to reduce adverse after-effects such as permanent disability, complications and death (4) . Clinicians have the moral obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harm while providing treatments or services to patients. Clinicians also have an ethical responsibility not to inflict harm on patients intentionally or through carelessness (5) . Preventing medical errors requires the establishment and management of value-based ethical environments. Such environments describe ethical policies that focus on employee’s commitment to values and norms related to practices (6) .

As reported by the Institute of Medicine, an estimated 44000 – 98000 deaths in the USA every year are attributed to medical errors (2) . Patient safety and quality of care are seriously affected by medical errors in hospitals. The epidemiology of medical error injuries remains a pressing global issue. In the United States, a recent report reviewing previous studies ranked unpleasant occurrences, especially medical errors, as the third leading cause of death (7) . In particular, up to 1.1% of hospital admissions have resulted in deaths due to medical errors. In 2013, more than 400,000 deaths were caused by medical errors (8) . In the UK, 101 medication errors occur per 1,000 drug prescription cases (9) , and it is also estimated that drug errors cause 12,000 deaths per year according to the National Health Service (NHS) (10) . The number of reported events increased from 135,356 between October and December 2005 to 508,409 during the same period in 2017 (11) .

Over the years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed patient safety guidelines to prevent medical malpractice, including Preventing Patient Fall , patient identification, hand hygiene, and safe surgery (12) . The Joint Patient Safety Group has introduced several patient safety goals to help healthcare providers create a safer environment for patients as well as themselves (13) . However, despite these efforts, the rate of medical errors leading to disability and significant mortality is high (14) . Moreover, we still encounter errors that have detailed guidelines dedicated to them and should not keep recurring. While emphasizing the enormous burden of harm to patients seeking treatment, the World Health Organization has stated that over the past 15 years, global efforts to reduce harm to patients have not been effective despite pioneering work in some healthcare centers (15, 12) .

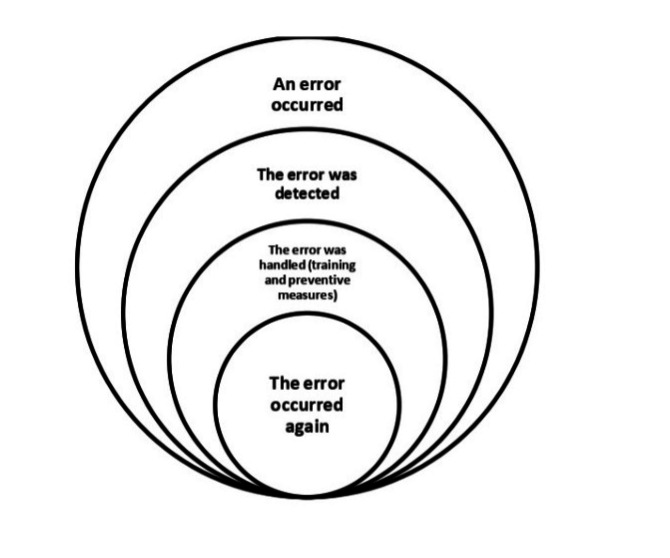

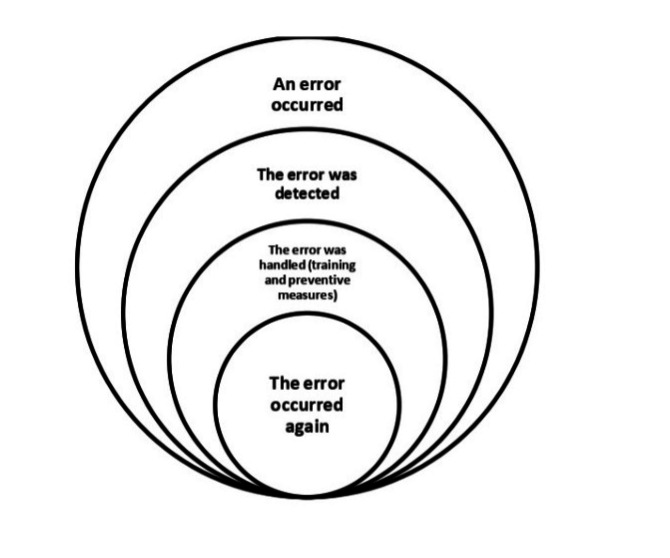

Recurrence of errors in this study refers to errors that 1) have been discovered once in the study environment, 2) are caused by factors that have been analyzed and for which specific preventive guidelines exist, and 3) continue to occur in spite of training and sensitization (Figure 1).

It appears that the measures currently being taken to reduce medical errors are not sufficiently coherent and need to be reviewed to prevent the recurrence of errors that occur frequently. Given the widespread efforts that have been made to prevent medical errors worldwide, the high frequency of errors has led to the hypothesis that there may be factors other than those currently known. Therefore, a scoping review was needed to identify the factors that have been considered at the international level in the field of error recurrence. This study aimed to identify international actions regarding factors related to the recurrence and prevention of medical errors in hospitals and to identify any existing knowledge gaps.

Two groups of results were found in the present study: A) Factors related to the recurrence of medical errors, and B) Strategies to prevent the recurrence of medical errors.

A) Factors related to the recurrence of medical errors

Two categories of human, and environmental and organizational factors were identified, along with six items, explained below.

Human factors

Fatigue: In some studies, fatigue has been identified as the most important cause of error and its recurrence (19, 23, 31). In one study, fatigue was reported as a contributing factor to anesthesia errors (28). Also, high workload and insufficient sleep lead to fatigue, which increases the frequency of mistakes (19,27, 30).

Stress: According to studies, stress is one of the most important factors in the occurrence and recurrence of medical errors (19, 23, 27, 42). We also found that people with neuroticism (including anxiety, anger, irritability, vulnerability and depression) were more likely to make medical errors (37).

Inadequate knowledge: Insufficient knowledge and skills are the most common cause of medication errors (21). In addition, inadequate knowledge can lead to stress and fatigue and increase medical errors (23). Studies conducted in the neonatal ward and operating room have shown that lack of sufficient knowledge and skills leads to the recurrence of medical errors (25, 43).

Environmental and organizational factors

Ineffective management: In this category, the following factors were found to lead to medical error recurrence: existence of strong authority in the organization that suppresses the possibility of identifying and learning from errors (43); expansion of hierarchical boundaries in an organization (such as a hospital) that requires a team structure (28); failure to provide timely and correct patient safety instructions and the results of Root Cause Analysis (RCA) to stakeholders (28, 38); lack of formal oversight of the implementation of safety protocols, and their failure to become an automatic part of the workflow of employees (28); not considering reminders (such as system alarms) and dependence on incomplete human memory, (28).

Various distractions: According to the studies, distraction of the medical staff caused by unnecessary visits to hospital wards, unnecessary telephone calls, staff irregularities, and irregular placement of equipment and medications, leads to surgical, anesthesia and medication errors (18, 23, 31).

Poor teamwork: Poor team communication is one of the most important factors in error recurrence and may cause harm to patients (25, 31, 43). Such weak connections are usually due to poor teamwork between physicians and nurses, which endangers patient safety (25, 43).

B) Strategies to prevent the recurrence of medical errors

According to the studies, six factors were identified as effective in preventing the recurrence of errors, including: 1) use of electronic systems, 2) attention to human behaviors, 3) workplace culture, 4) proper workplace management, 5) training, and 6) paying attention to teamwork.

Use of electronic systems: The findings of several studies have emphasized the importance of using electronic systems such as CPOE (Computerized Provider Order Entry) and barcode systems to prevent the recurrence of errors (14, 19, 21, 23, 28, 32, 46). The barcode system can reduce misdiagnosed drugs, prevent misidentification of the patient and misuse of time, and reduce missed and wrong dose errors (46). Therefore, the installation of barcoded wristbands for all patients should be considered at the time of admission (21). Also, e-prescriptions significantly reduce medication errors and do not put patients at risk for illegible handwriting and related causes (23). Such technologies do not replace specialists involved in patient care, but rather organize information and allow specialists to perform valuable tasks such as complex decision-making and communication while the system performs repetitive and tedious tasks (26).

Attention to human behaviors: Numerous studies have addressed human factors and behavioral issues as a strategy to prevent the recurrence of errors (19, 24, 31, 33, 36, 37, 40, 43). Based on one study, extrovert, conscientious people with strict work ethics committed fewer errors, and those with problem-solving skills did not commit medical errors (37). In addition, the ability to think systematically plays a role in reducing the incidence of medical errors (36). Several studies have found a significant relationship between having a deep understanding of anthropological factors and a reduced amount of incurring “never events” (33, 43). Moreover, in order to eliminate human errors, we should have knowledge of human behaviors and consider the two categories of schematic behaviors and attention-related behaviors. Schematic behaviors are reflective and can be considered in error reduction by using checklists and attracting public attention. Attention-related behaviors, on the other hand, are related to problem-solving skills, and are therefore more difficult to control and require professional supervision and training to reduce errors (34). In some studies, individual and organizational responsibility and accountability have been found to be effective in reducing errors (24, 31, 40).

Proper workplace management: One of the main components of management is supervision. Some procedures that have prevented the recurrence of errors include continuous audits, implementation of powerful documentation such as valid checklists for safe surgery and anesthesia (31, 32, 39), and strict supervision of compliance and corrective measures (28). Proper alignment of forces and increased use of experienced and more educated staff have also been effective in preventing errors. Examples of such measures include increasing the working hours of RN nurses and reducing the working hours of LPN nurses. Also, increasing the number of nurses has reduced the rate of patient fall (13). Hospitals can also help reduce medical errors through stronger and more reliable safety management, including error reporting, learning from errors, information transparency, and providing timely error feedback (23, 43).

Workplace culture: According to studies, medical errors will be reduced in the presence of proper workplace culture (22, 28, 30, 34, 39, 44). In one study, a positive relationship was found between workplace culture and learning from errors (39), and other studies have identified a positive relationship between culture and teamwork (22, 44).

Training: Numerous studies have shown that training in different areas is effective in preventing errors (20, 32, 34, 35, 39, 46). Studies have emphasized the importance of including error training in the university curriculum as part of the education of medical staff to fully acquaint them with the issue before starting work, stating that this will ultimately help reduce medical errors (34, 46). Training campaigns with varied and specific topics in the field of patient safety have been very useful in reducing errors (for instance the campaign of “sign your site”) due to the extent of these campaigns (20, 32, 35). In addition, using educational models such as the Potential Risk Assessment Model (26) and the Eidenhaven Classification Model (14) will improve learning from errors and reduce medical errors. Although RCA is used to provide solutions to prevent the recurrence of errors, it appears that this method cannot prevent errors from recurring (38, 45). One study found that physicians’ participation in RCA recommendations was low (38) and that the RCA often provided recommendations that replicated existing policies or previous recommendations (38, 45).

Paying attention to teamwork: Doing the right thing as a team is effective in preventing mistakes (28, 31, 32, 41, 44). Teamwork is especially significant between physicians and nurses, and in areas such as the operating room and among the surgical team members (28, 31, 37, 41). Therefore, various team-building programs can be used to increase teamwork skills among staff (28).

1.

Vaziri S, Fakouri F, Mirzaei M, Afsharian M, Azizi M, Arab-Zozani M. Prevalence of medical errors in Iran: asystematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]2.

Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]3.

Askarian M, Sherafat SM, Ghodsi M, et al. Prevalence of non-reporting of hospital medical errors in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(11):1339–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]4.

Bates DW, Singh H. Two decades since to err is human: an assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(11):1736–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]5.

Bonney W. Medical errors: moral and ethical considerations. Journal of Hospital Administration. 2014;3(2):80–8. [Google Scholar]6.

Rathert C, Philips W. Medical error disclosure training: evidence for values-based ethical environments. Journal of Business Ethics. 2010;3(97):491–503. [Google Scholar]7.

Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the us. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]8.

Van Den Bos J, Rustagi K, Gray T, Halford M, Ziemkiewicz E, Shreve J. The $17.1 billion problem: The annual cost of measurable medical errors. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4):596–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]9.

Sutherland A, Canobbio M, Clarke J, Randall M, Skelland T, Weston E. Incidence and prevalence of intravenous medication errors in the UK: a systematic review. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2020;27(1):3–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]11.

Ahsan A, Setiowati L, Noviyanti LW, Rahmawati IN, Ningrum EH, Putra KR. Nurses’ team communication in hospitals: a quasi-experimental study using a modified TeamSTEPPS. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(2):2157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]13.

Bowden V, Bradas C, McNett M. Impact of level of nurse experience on falls in medical surgical units. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(4):833–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]14.

Brandao P, Rodrigues S, Nelas L, Neves J, Alves V. [ Adverse events and near misses in medical imaging] Acta Med Port. 2011;24(1):169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]15.

Charpiat B, Bedouch P, Conort O, Rose FX, Juste M, Roubille R. [ Opportunities for medication errors and pharmacist’s interventions in the context of computerized prescription order entry: a review of data published by French hospital pharmacists] Ann Pharm Fr. 2012;70(2):62–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]16.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]17.

Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth . 2020;18(10):2119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]18.

Flynn EA, Barker KN, Gibson JT, Pearson RE, Berger BA, Smith LA. Impact of interruptions and distractions on dispensing errors in an ambulatory care pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(13):1319–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]19.

de Carvalho M, Vieira AA. [ Medical errors in hospitalized patients] J Pediatr (Rio J) 2002;78(4):261–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]20.

Meinberg EG, Stern PJ. Incidence of wrong-site surgery among hand surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(2):193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]21.

Berman A. Reducing medication errors through naming, labeling, and packaging. J Med Syst. 2004;28(1):9–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]22.

Meaney ME. Error reduction, patient safety and institutional ethics committees. J Law Med Ethics. 2004;32(2):358–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]23.

Deans C. Medication errors and professional practice of registered nurses. Collegian. 2005;12(1):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]24.

Ziv A, Ben-David S, Ziv M. Simulation based medical education: an opportunity to learn from errors. Med Teach. 2005;27(3):193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]25.

Jirapaet V, Jirapaet K, Sopajaree C. The nurses’ experience of barriers to safe practice in the neonatal intensive care unit in Thailand. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(6):746–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26.

Hovor C, O’Donnell LT. Probabilistic risk analysis of medication error. Qual Manag Health care. 2007;16(4):349–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]27.

Hakimzada AF, Green RA, Sayan OR, Zhang J, Patel VL. The nature and occurrence of registration errors in the emergency department. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(3):169–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]28.

Agrawal A. Counting matters: lessons from the root cause analysis of a retained surgical item. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(12):566–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]29.

Frith KH, Anderson EF, Tseng F, Fong EA. Nurse staffing is an important strategy to prevent medication errors in community hospitals. Nurs Econ. 2012;30(5):288–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]30.

Steyrer J, Schiffinger M, Huber C, Valentin A, Strunk G. Attitude is everything? the impact of workload, safety climate, and safety tools on medical errors: a study of intensive care units. Health Care Manage Rev. 2013;38(4):306–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]31.

Barrington MJ, Uda Y, Pattullo SJ, Sites BD. Wrong-site regional anesthesia: review and recommendations for prevention? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28(6):670–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]33.

Stein JE, Heiss K. The Swiss cheese model of adverse event occurrence-closing the holes. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2015;24(6):278–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]34.

Chiarini M, De Vita E, Meggiolaro A, et al. [Errors in medicine: perceptions of nursing students in Rome] Prof Inferm. 2017;70(4):206–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]35.

Hartford J, Harrington S. Overcoming a ‘never event’, a completed audit cycle of ‘stop before you block’. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2017;42(5):e152–e3. [Google Scholar]36.

Hwang JI, Park HA. Nurses’ systems thinking competency, medical error reporting, and the occurrence of adverse events: a cross-sectional study. Contemporary Nurse. 2017;53(6):622–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]37.

Babaei M, Mohammadian M, Abdollahi M, Hatami A. Relationship between big five personality factors, problem solving and medical errors. Heliyon. 2018;4(9):e00789. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]38.

Vrklevski LP, McKechnie L, OʼConnor N. The causes of their death appear (unto our shame perpetual): why root cause analysis is not the best model for error investigation in mental health services. J Patient Saf. 2018;14(1):41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]39.

Abbasi F, Pazokian M, Borhani F, Nasiri M. Correlation between workplace culture, learning and medication errors. Revista Latinoamericana de Hipertension. 2019;14(1):102–13. [Google Scholar]40.

Tigard DW. Taking the blame: appropriate responses to medical error. J Med Ethics. 2019;45(2):101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]41.

Lee YJ, Hwang JI. Relationships of nurse-nurse collaboration and nurse-physician collaboration with the occurrence of medical errors. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. 2019;25(2):73–82. [Google Scholar]42.

Honno K, Kubo T, Toyokuni Y, Ishimaru T, Matsuda S, Fujino Y. Relationship between the depressive state of emergency life-saving technicians and near-misses. Acute Med Surg. 2020;7(1):e463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]43.

Koleva SI. A literature review exploring common factors contributing to never events in surgery. J Perioper Pract. 2020;30(9):256–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]44.

Latzke M, Schiffinger M, Zellhofer D, Steyrer J. Soft factors, smooth transport? the role of safety climate and team processes in reducing adverse events during intrahospital transport in intensive care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2020;45(1):32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]45.

Martin-Delgado J, Martinez-Garcia A, Aranaz-Andres JM, Valencia-Martin JL, Mira JJ. How much of root cause analysis translates to improve patient safety. a systematic review. Med Princ Pract. 2020;29(6):524–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]46.

Anonymous Reducing medication errors requires a multifactorial approach. Drugs and Therapy Perspectives. 2004;20:22–5. [Google Scholar]47.

Sorrell JM. Ethics: ethical issues with medical errors: shaping a culture of safety in healthcare. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2017;22:2. [Google Scholar]48.

Noland CM, Carmack HJJQHR. Narrativizing nursing students’ experiences with medical errors during clinicals. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(10):1423–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]49.

Pezzo MV, Pezzo PP. Physician evaluation after medical errors: does having a computer decision aid help or hurt in hindsight? Med Decis Making. 2006;26(1):48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

When an unexpected medical injury occurs, the consequences can be life-altering. Patients and their families often find themselves overwhelmed, confused, and searching for answers—and justice. If you’re looking for the best medical malpractice attorney in OKC, you need more than a lawyer. You need an advocate who understands the complexities of both medicine and law, someone who will stand up to hospitals, corporate healthcare systems, and powerful insurance companies.

When an unexpected medical injury occurs, the consequences can be life-altering. Patients and their families often find themselves overwhelmed, confused, and searching for answers—and justice. If you’re looking for the best medical malpractice attorney in OKC, you need more than a lawyer. You need an advocate who understands the complexities of both medicine and law, someone who will stand up to hospitals, corporate healthcare systems, and powerful insurance companies. A Strategic, Evidence-Based Approach

A Strategic, Evidence-Based Approach

Source: National Library of Medicine:

Source: National Library of Medicine:  Medical errors are unavoidable occurrences in health systems that can adversely affect patient safety (1) . Years after the American Institute of Medicine’s prominent report, “To Err Is Human” (2) , which addressed the importance of medical errors for the first time, there are still serious concerns about patient safety (3) .

Medical errors are unavoidable occurrences in health systems that can adversely affect patient safety (1) . Years after the American Institute of Medicine’s prominent report, “To Err Is Human” (2) , which addressed the importance of medical errors for the first time, there are still serious concerns about patient safety (3) . Medication errors are the common causes of patient morbidity and mortality. It adds financial burden to the institution as well. Though the impact varies from no harm to serious adverse effects including death, it needs attention on priority basis since medication errors’ are preventable.

Medication errors are the common causes of patient morbidity and mortality. It adds financial burden to the institution as well. Though the impact varies from no harm to serious adverse effects including death, it needs attention on priority basis since medication errors’ are preventable. 1,2

1,2 Have you ever been to a doctor with a health problem, only to find out later that the diagnosis was wrong or delayed? If so, you are not alone. Misdiagnosis is a common and serious problem in medicine that affects millions of patients every year. According to some estimates, up to 20% of medical cases are misdiagnosed, leading to unnecessary suffering, disability, and even death. In this article, we will explore the causes, consequences, and solutions.

Have you ever been to a doctor with a health problem, only to find out later that the diagnosis was wrong or delayed? If so, you are not alone. Misdiagnosis is a common and serious problem in medicine that affects millions of patients every year. According to some estimates, up to 20% of medical cases are misdiagnosed, leading to unnecessary suffering, disability, and even death. In this article, we will explore the causes, consequences, and solutions.